Derek Grzelewski : Writer : Photographer : Adventurer

| |

| Home |

| Current Articles |

| About Derek |

| Photos |

| Adventure Blog |

| Seminars |

| Books |

| Fly fishing |

| Contact |

THE TROUT DIARIES

A year of fly fishing in New Zealand

By Derek Grzelewski

“I fish because . . . in a world where most men seem to spend their lives doing things they hate, my fishing is at once an endless source of delight and an act of small rebellion; because trout do not lie or cheat and cannot be bought or bribed or impressed by power, but respond only to quietude and humility and endless patience; because I suspect that men are going along this way for the last time, and I for one don't want to waste the trip . . . .”

Robert Traver, Anatomy of a Fisherman

“All good things—trout as well as eternal salvation—come by grace and grace comes by art and art does not come easy.”

Norman Maclean, A River Runs Through It

“I only cast when I have to.”

Marc Hertault

Chapter 1

The creek was a perfect trout stream, a staircase of pools and riffles, defined and stable, remote and little known, brimming with potential and promise. It cut deep into the Otago farmland, and the banks that framed it were like miniature escarpments. Sheep had worn tracks along both edges, affording easy walking and excellent vantage points from which to search the water. It was the kind of place where you’d expect trophy brown trout to be sitting high in the water in their prime lies, undisturbed and feeding eagerly.

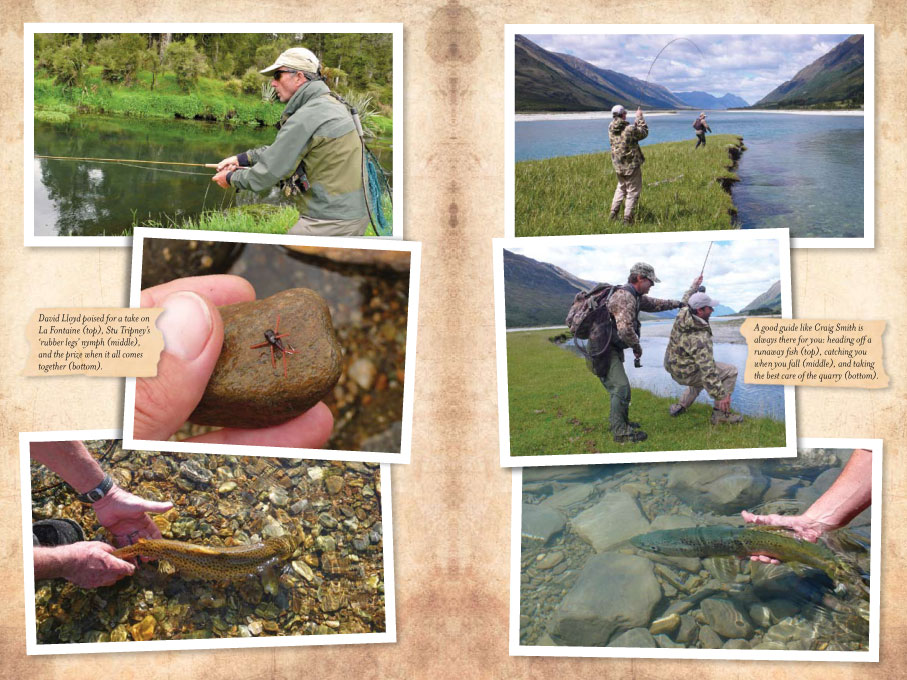

My angling compadre, David Lloyd, and I had never fished this creek before, but we were eager to explore new waters. The past three days of our annual early-season pilgrimage had been the best we’d ever had on our favourite River X. The fish were active and plentiful, and almost embarrassingly easy in what is usually tough water. Each day had been better than the one before, and we knew we could not sustain this level of success. Our exceptionally good fortune would inevitably come to an end, so we decided to pocket our winnings and change venues, start afresh on new water, with a clean scoreboard and innocent hopes.

The weather, too, was deteriorating. After nearly a week of sunshine, a slab of bruise-coloured clouds, heralding heavy rain and rivers in spate. This was the calm before the storm, surely our last day of fishing on this trip. Still, despite the heavy skies, this gem of a creek had us buzzing with anticipation. There had to be trout here, surely not as plentiful as in our River X, but that would be fine by us. We were after quality, not numbers. The creek was a dream and we were living it. It was only a matter of time, short time, before we found a feeding fish.

We walked slowly, our eyes X-raying the water, following feedlines and the seams of colour change along the bottom, dissecting the fast broken riffles, looking for what David called the “soft shadowy shapes.” Our rods were rigged up for all possibilities, David’s with double nymphs and a white yarn indicator, mine with a light taper line and a dry fly, the first-choice Parachute Adams. The creek unfolded before us like a good tale, one turn at a time, and we had it to ourselves, all of it, all the way to the forest, a long day’s fishing away. Our imaginations worked overtime, conjuring double-figure fish and screaming reels. Surely, if such things were to happen, this was the place and time.

But strangely, we were not seeing fish. Not a single one. We were not spooking any, either, which was the more disturbing of the two. Hunters who are flushing out their quarry are at least getting close to it. They can hone their skills, walk more stealthily, look further ahead. But not seeing the quarry at all dilutes the concentration and makes the attention wonder. It also brings about a peculiar kind of heavy-hearted despair and doubt. Lots of doubt.

Was it us or the fish? Were they simply not here, or were we not seeing them? Had someone fished the creek today already? Had the water been polluted by some upstream dairy farm, so that it only looked perfect but was in fact lifeless?

In creeks like this it is unreasonable to expect fish in every pool. This kind of water falls into a category which the guidebooks describe with “long walks required between fish.” So we walked, and looked, hour after hour. We ate lunch in silence, sitting on a high bank overlooking yet another perfect pool, never taking our eyes off the water and never seeing a thing that even remotely looked like a trout.

At times like these, you begin to think that, completely without reason and despite all past experiences, you are never going to catch another fish. Botched presentations, refusals and missed takes are all fine, part of the game. But not getting even a single opportunity for all the miles we’d already put in was just too disheartening. Especially on the water that promised so much.

I was beginning to lose interest, walking faster and more carelessly, paying less and less attention to the water, which in sight-fishing is the beginning of the end. Then David grabbed my sleeve, his rod tip pointing up and across the creek to a feedline beneath the opposite bank.

“There,” he said almost reverently. “A rise, if I ever saw one.”

Then to himself he added: “And why am I whispering?”

It was as if the sun had come out, in an instant changing our internal weather, dispelling the gloom, lighting everything with vibrant colours. A miracle had just occurred, dispelling all doubt and despair. We had found a fish, and it was feeding. Right now, there was nothing more we asked of the world.

It was a clean emerger rise, with no part of the fish breaking the surface, only a soft dimple and a few air bubbles. I tied on a Cul de Canard emerger and offered the rod to David.

“No, I’d only fuck it up,” he said. “You go. No pressure though.”

It was nearly four o’clock, and in all likelihood we’d not find another fish today. No pressure indeed.

The day was still windless and I had a #4 double-taper line on a # 6 rod, a trick I’d learnt from one of the old-timers on our River X. The rig requires you to adjust your casting technique, but done right it is capable of unsurpassedly delicate presentation, especially with a dry fly. I waited for the fish to rise again. It did and I had its position pin-pointed.

For a moment I thought it would be interesting to have been wearing one of those heart-rate monitors that are all the rage in aerobic fitness training. Judging by the pounding in my ears, the thing would surely be spiking in the red zone, right up there with an uphill sprint. I took a deep steadying breath, let all the nonsense fall away and began to cast.

I made the first cast deliberately short, both to straighten the line and to better judge the distance. Then, with all the skills and calm I could muster, I placed the tiny emerger into the feedline, a good metre ahead of the fish.

The rise was another soft dimple, as if a drop of rain had fallen into the water. But as I lifted the rod I felt the weight of the fish, solid and alive. David yelled an inarticulate cry of victory, the fish leaped, flashed silver in the overcast light, then tore off upstream and took another big air, shaking itself head to tail with fury. It hit the surface of the pool with a flop and the line went slack.

It took a few more pounding heartbeats for the senses to register, then to accept that the fish was gone. The intensity of the moment was punctured. I sat on the bank—it is easier to shake sitting down—and watched the slack line drifting past me. I pulled it in and saw that the emerger was still on, its punk stem brilliantined with mucus. The fish had not broken me off, it simply shook out the hook on the jump.

There was not much to say, but we both agreed to call it a day, and walked back to the truck, each lost in his own silence. It was only later that night, by the fire in a classic rural Otago pub, that we dared to talk about what happened.

“You know, of all the fish we’ve caught, or tried to catch—ever—that was the one I’ll remember most,” David said. “Today we struck pure gold, a few pounds of it. Forget about trophies and numbers. That was what it is all about: magic moments like that.”

Outside it was already raining heavily, and the storm gusts sounded like fistfuls of lead shot thrown against the windows. The fishing was over for a week or more, but that did not matter. David was right. A dozen fish would not have made the day more memorable. The magic moment was earned and ours, a trophy to keep, and a reason to walk more riverbanks in the hope of one day living it again.

Trout, and the rivers and lakes where they are found, have a way of drawing the fly fisher to them, deeply and inextricably. What begins as a weekend hobby soon becomes a way of life. It dictates the kind of car you buy, the colour of your clothes, the roads you choose to travel to places, the people you spend most time with, sometimes even the jobs you take. Once the rivers lure you in deeply enough, they redefine your personal geography, too, so that it’s no longer based on towns, cities and roads that connect them, but on rivers, lakes, watersheds and directions of flow. At this stage, every time you cross a bridge you cannot help but to slow down even if for the quickest of looks, even if you have no fishing gear with you—though by now it’s likely your rod and vest are as inseparable from your vehicle as the jack and the spare wheel.

Yet despite, or perhaps because of, their abiding allure, trout themselves remain mysterious and unpredictable creatures, making the fishing for them a complex and open-ended affair. My friend and long-time fly fishing mentor, Wanaka guide Ian Cole—a man who spends more time on the water than just about anyone else I know, and who has converted his entire walk-in wardrobe into a storage place for rods and fly-tying materials—once told me: “The more I fish for trout, the less I know about them.” He did not have to add “and the more I want to know.” That went without saying.

I, too, have been drawn into the pursuit of trout—slowly at first, flirtatiously almost, until over some ten years ago I found myself spending so much time on the water that I decided I might as well become a guide; turn the passion into a dream job.

This, I now realise, was a mistake, because good guiding has little to do with being a good fisherman, and people who say that “the worst day’s fishing is still better than the best day at work” have clearly not fully experienced either.

Guiding can be both extremely rewarding and it can numb your soul. A guide is at once a paid companion and a confidante, a cook, chauffeur and paramedic, a fish and human psychologist, a problem-solver and sometimes just a straight-out trout pimp. Don’t get me wrong. I’m not against guiding, not any more, though at one point I used to think that catching a fish while being guided was like hearing a punch line without the rest of the joke, a moral without the story. Some of my closest friends are guides, and they are as fine human beings as they are expert anglers. They have to be, because out of a hundred or so days in the season there are only a few when it all comes together perfectly. For the rest of the time a good guide has to be both a compassionate nurse and a miracle maker.

Ultimately, though, the point of fly fishing for trout is to guide ourselves through the complexities of the sport, its highs and lows, joys and frustrations, nuances and mysteries. In this journey trout is more a direction than a goal, because no matter how much you learn and how good a fly fisher you become, there are always surprises, both those that delight and those that humble. And still there is more, always more, because trout and their ways can never be fully known, and for that, too, we must be eternally grateful.

Ever since Zane Grey, the American writer of romance westerns, fly fished in New Zealand in the 1920s and declared the country to be the Angler’s Eldorado, trout enthusiasts from around the world—members of what Izaak Walton called the Brotherhood of the Angle—have been making pilgrimages to the rivers and lakes of both islands, and for a good reason. Nine decades after Grey’s visits, New Zealand remains the country of trout, a dream destination for anyone with a passion for a fly rod, even if all too often New Zealanders still need foreigners to remind them of that.

There may be bigger fish elsewhere—Oregon steelheads, the sea-run trout of Patagonia—but for sheer diversity and quality of fishing for wild brown and rainbow trout, New Zealand remains unsurpassed. This is why the town of Gore, at the bottom of the South Island, built a monument to the fish and proclaimed itself the brown trout capital of the world, while Turangi, where the Tongariro River enters Lake Taupo in the North Island, did the same with rainbow trout. To us New Zealanders, who favour the understated over the bombastic—Ed Hillary’s “We knocked the bastard off” over Neil Armstrong’s “one giant leap for mankind”—such boastings may seem naff and pretentious, a tourism promoters’ boast. With any luck, one day we may finally get the fact that the boast is itself an understatement.

All it takes is someone like David Lloyd to tell the story of his father, a life-long angler who fished the ponds and streams of England with regularity and passion. He was a competent caster and an avid fly tier, but he had never caught a trout over three pounds. What in New Zealand we would call “just a wee fella, about three pounds” for David’s father would have been a trophy, a fish to remember for the rest of his days.

Still, even with such reminders, in New Zealand it is all too easy to take the exceptional for normal, the gift for the given; to assume that the rivers and the trout as we know and love them will still be there tomorrow, and that we will be here to enjoy them. It often takes something that shakes our world out of its comfort, ruts and patterns of predictability—a collision, an accident or illness—to show us the impermanence of all things and how foolish it is to assume anything at all. For me, it happened on a river with Henry Spencer.

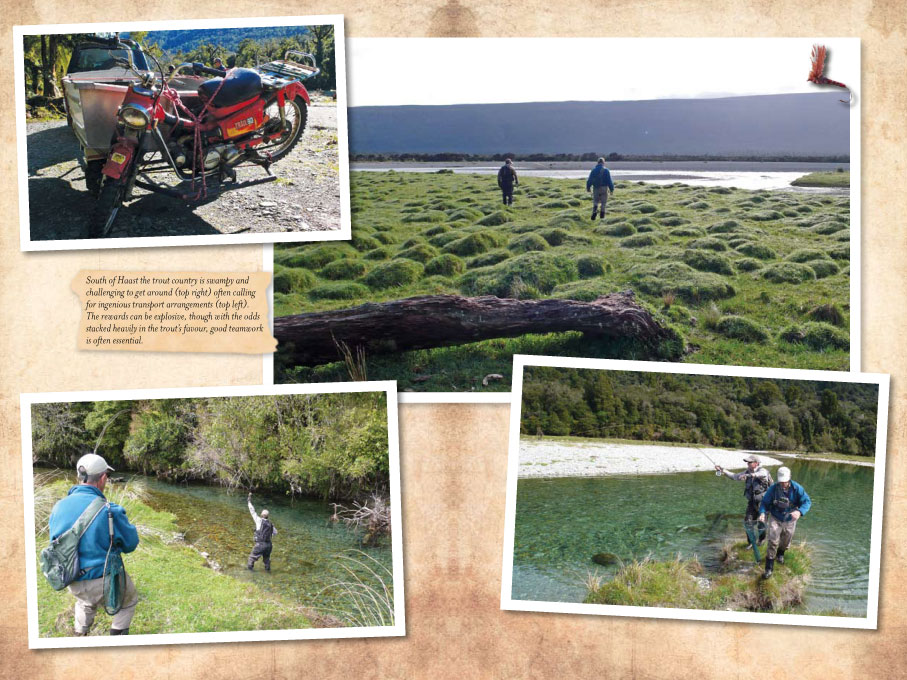

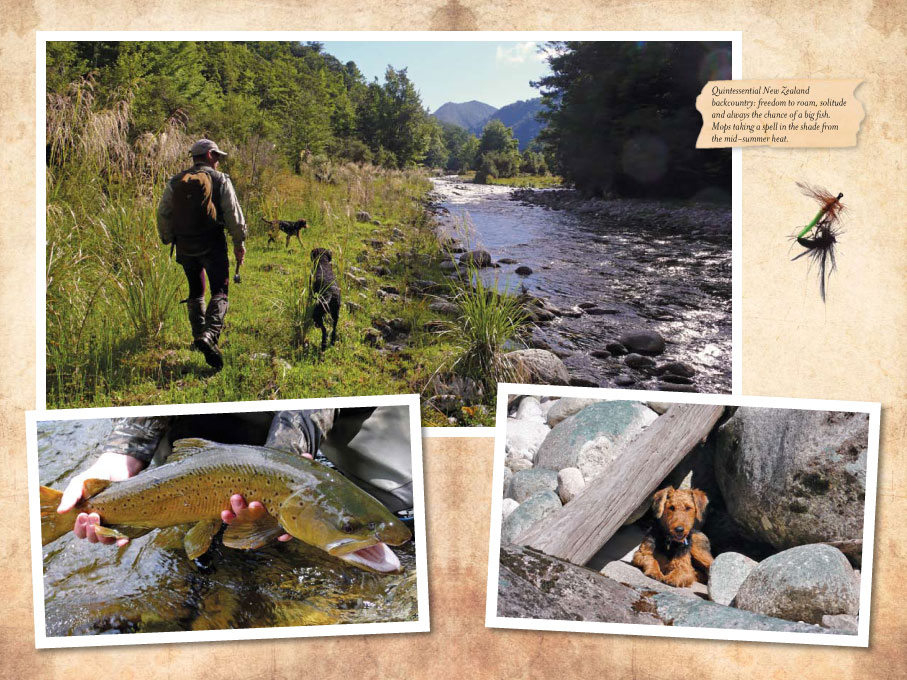

There is a vagrant population of fly fisherman and women in New Zealand—retirees, lifestylers, most of them seasonal migrants from overseas—and if you roam and fish the country long enough you invariably begin to bump into them as they follow the season to wherever the fishing is best at the time. Some people call them trout bums. I’ve come to call them—us—trout bohemians, and Henry Spencer was certainly one of movement’s exemplars.

I first met him on the Eglinton River in Fiordland. He was a quiet and gentle man in his early 60s, private and self-content, immaculately decked out in a crisp sea-blue shirt and matching tan-coloured waders and vest, both of which seemed tailor-made, and happier on a river than in any other place he could imagine himself to be. After a calm morning, a nor’wester had kicked in, quickly turning into a downstream howler, making spotting fish and casting impossible. I was coming down the river and back to my camper when I met Henry, who, far from being frustrated by the headwind, simply turned around, changed his dry-fly and nymph rig to a streamer—the ubiquitous olive Woolly Bugger—and began to fish downstream, with the wind and the current.

As I passed, I invited him for a drink in my camper, and eventually he succumbed, though only after the wind grew so strong it became impossible not just to cast but even to keep the fly line in the water. In the camper, nosed into the gale and rocking like a boxer looking for an opening, we drank Ethiopian coffee and talked fishermen’s talk, about places, rivers and flies, about the most memorable fish.

Henry never said much about himself, though I gleaned he was a retired teacher from somewhere in the American Midwest, that he was a widower and that his two daughters were happily married. I always thought of him as a Dead Poets Society kind of teacher, though calmer and less flamboyant than the Robin Williams character. He drew a tight circle around his private life, but he delighted in debating anything to do with trout, rivers and fly fishing, and always he had things to say, good and thought-through things that come not from books but from first-hand experience.

For him, New Zealand was the greatest find of his life, a new world of fishing possibilities, and laughingly he talked of himself as the trout Columbus discovering his own personal Terra Trutta. Over the years, I’d bump into Henry two or three times a season: on a West Coast spring creek, on the Buller River near St Arnaud, on the Mataura in Athol, once or twice on the Tongariro. Then, last year, as we sat on our green fold-out chairs on the bank of the Inangahua River, outside Reefton, Henry, unusually for him, told me some more about himself. The news was not good.

Only a couple of months earlier, he said, he’s been diagnosed with a terminal cancer. The medical specialists advised chemotherapy, though more as a delay of the inevitable than a cure. They gave him six months; a year if he was lucky.

Henry’s face was pale as he talked, but his eyes were still bright—perhaps not with their usual gentle fire but with some fierce inner resolve. He had organised his affairs, he told me, tied up all the loose ends, sold his possessions, written up a will. But he would not subject himself to the chemo, he said. He would not end his life vegetating on a life-support system, waiting for some merciful person to turn it off. No, he would end it here, on a river in New Zealand, and he would fish every day until the Reaper came, and when the moment arrived he would be ready for it and would welcome it, knowing that he had lived well and did what he loved until the end.

He even wrote a letter in case a stranger found him dead on a riverbank. One copy he carried in his vest with his fishing licence; the other he taped to the dashboard of his forest-green Subaru. The letter, he said, explained that it was all right, that this was what he had planned.

“Don’t want any poor fella to panic or blame himself,” Henry said. “There is nothing anyone can do, including me.”

What can you say to such an announcement? Consolations seemed trivial, reassurances empty. I said I was sorry (what a useless word that is) and that if he had to, this was certainly a fine way to go. I looked towards the river, hoping for something, a rising fish perhaps, something that would break the gloom, offer a diversion. But the river was quiet, and the silence heavy, and we sat without any more words, nursing our drinks until the night came.

That last encounter with Henry left me rattled and restless. It sent me re-examining my own ways and priorities, and above all looking at the long list of “things to do before you die,” many of which had to do with fly fishing. There were famous and not-so-famous rivers I wanted to explore at particular times of the season, and people I wanted to fish them with. These trips and visits, long and often promised and discussed, had somehow always managed to get postponed in the knowledge that there would surely be another time, perhaps a better time, after we dealt with what was immediate and seemingly important.

But what if there was no more time, no next year, future season, better weather? What if, as in Henry’s case, each day, each river, each cast or fish might be the last one? What would that do to the way I fished? The way I lived? These thoughts were not morbid but sobering. They put my days on a river into sharper relief, gave them a kind of carpe diem intensity.

Thus the idea for this diary was born. Where would I go, what would I do, I asked myself, if, like Henry, I had this one last season to fish? It did not mean I’d fish all day every day, confusing, as it were, mileage with meaning. I learned long ago that the hours we put in to an activity do not always translate into the intensity of experience. Nor are the size or number of fish caught a qualifying factor. This was more about collecting trophies of a different kind: sensory snapshots of unforgettable fish, moments of riverside magic like the single trout on the nameless creek I hooked and lost with David, moments that never fade from memory; the kind of trout experience that puts a goofy smile on your face or makes your eyes glaze over into that thousand-yard stare every time you think of them.

Living in New Zealand, I was already in the best possible place on the planet to conduct such experiment, but which rivers and places would I choose? Which events in the trout calendar would I want to witness and participate in?

Though I’ve fished a lot and often, that elegant circular continuity to the trout’s year had so far eluded me, and closing that circle would make a worthwhile quest. It has to do with the life cycles of the trout’s food, the seasons and spawning patterns, the way a river can be full of feeding fish one month, and another be completely empty, and with the knowing which month was which. At its heart, fly fishing is as much about understanding trout as catching them, about solving riverside riddles and glimpsing a greater unknown that is far more satisfying than the relatively simply act of hauling in a lump of meat.

Silently thanking Henry for this jolt of inspiration, I made an inventory of my gear, restocked my fly boxes, studied my maps and began to pencil in tentative dates. Then, of course, life intervened with its deadlines, commitments and other must-dos, and for a while it seemed I was back to the old patterns and routines, as if the “get up and live” edict Henry had unknowingly given me had never happened. Yet fate had already written my own “Mack truck” experiences into the trout diary, though I did not see them coming or have any indication of their collision course. You never do. They always seem to blindside you when you least expect them.

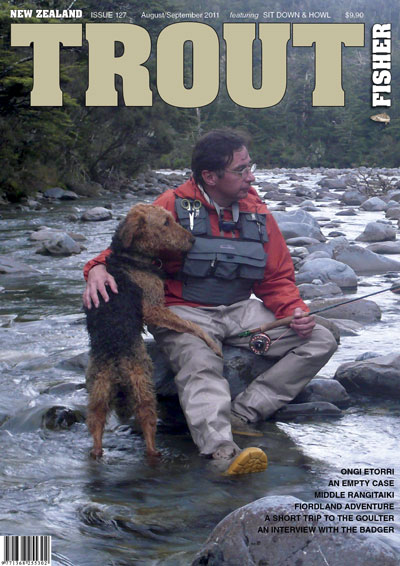

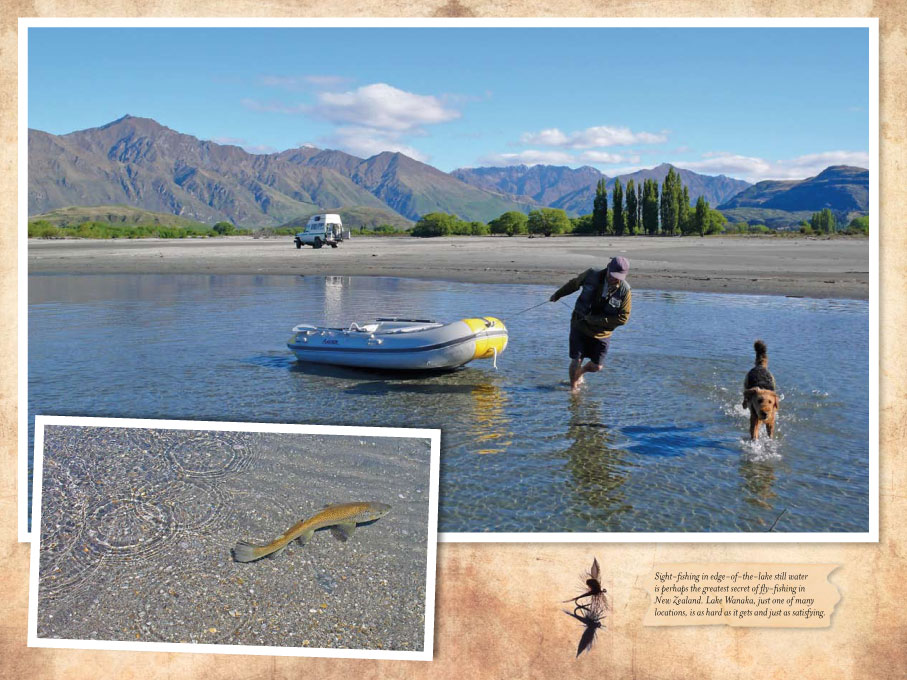

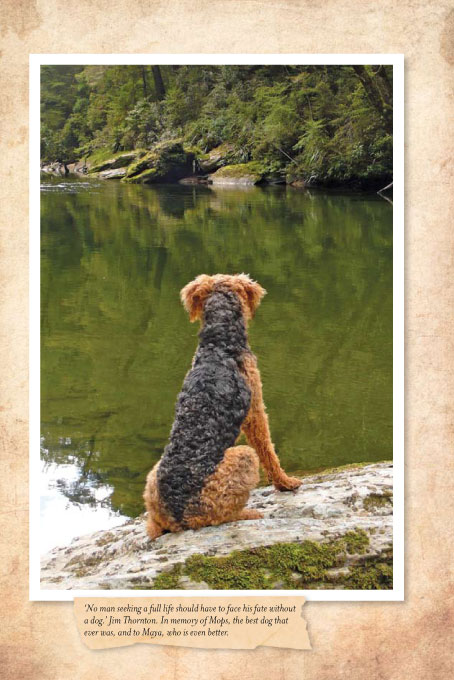

The season was only two weeks away, opening-day fever already palpable in the local tackle shop, and I was still making plans. I thought I’d let that short-lived fever pass, as I always did, before heading out on my first adventure. But then, walking my Airedale terrier Mops along the fishermen’s track that parallels my home river, the Clutha, I saw the Deleatidium mayfly hatch, brown and dainty. And I watched the trout, still famished from spawning, rise to gorge on them on so eagerly they did not seem to go back down under after taking each fly but surfed the current with their mouths open, their golden-brown bodies partly above the water at all times.

I thought of Henry. He would not wait, plan around the weather, the conditions, the possibility of crowds. He would simply go and fish, regardless. Right now, he would be trotting to the car to get his gear , assembling the rod on his way back to where the fish were rising, knowing that the trout would rise again another day but that he might not necessarily be there to see it. The clock was ticking, and he was only too aware of it. The time to fish was now, not at some future date pencilled into the diary and subject to this, that and the other contingency and constraint. And so I began packing my camper, and later that night I called a friend with an offer I knew he could not refuse.

Available now in all good bookstores and online: